The Tell-Tale Art

Stephen Mancusi, illustrator, helps put the bad guys behind bars

By Robin Catalano

Dead men, it seems, do tell tales.

This is the lesson that Stephen Mancusi ’81 has learned in twenty-seven years as a forensic artist with the New York Police Department. The recently retired first-grade detective has seen enough of the strange, the macabre, and the unbelievable to fill volumes, all in a career he never really meant to pursue in the first place.

Mancusi, a Brooklyn native, had an early inclination toward drawing, and attended FIT in preparation for becoming a professional illustrator. He credits the structured program with developing a high level of technical skill, and fondly remembers several of his teachers. “Mr. Baxter gave me the illustrative process—how to develop it, how to do the research, how to create the sketches,” the affable Mancusi recalls. “Morton Kaesche brought out the best in me—there’s no question about it. I have some images I did in his class that I still hang in my studio for inspiration. And Mr. Pimsler, I kept a little friendship with him over the years. The instruction was invaluable for me.”

One summer, several of Mancusi’s friends signed up for the civil-service exam, and on a whim, he decided to join them. He did so well on the test that through most of his college years, the police department kept trying to recruit him. “I had no intentions of ever being a police officer,” Mancusi says in his jovial Noo Yawk accent. “I wanted to be an artist. But it’s not easy to get work.” With a young family to support, the lure of a steady paycheck won out, and he went through police-academy training and street service. Within a couple of years, a position opened in the composite art unit. Mancusi jumped at the opportunity, and it wasn’t long before he became part of a select group of full-time forensic artists—he estimates that there are less than a hundred even today—and one of the most respected.

Although composite art—a facial sketch of a suspect, based on witness descriptions—is the best-known type of forensic art, the field has expanded to include a variety of other artistic renderings (see sidebar). The artist will probably never be replaced, but the technology used to produce the work has changed dramatically since computers first became widespread in the early 1990s. Mancusi cautions, “You can’t be a forensic artist or any kind of illustrator without having digital capabilities. Everything I do, painting or drawing, will end up being digital at some point.”

Still, for composite sketches, of which he’s drawn thousands, and which require a subtlety that Photoshop and Illustrator can’t capture, Mancusi begins with pencil and paper. The process is time-consuming and difficult, requiring the artist to test not only his illustrative skills, but also his interpersonal ones. Many times, the artist must interview a witness who was the victim of a crime only twelve hours before. Kenneth Calvey, the retired Commanding Officer of the NYPD Latent Prints Section, who worked with Mancusi for twenty years, comments, “Steve has the natural ability to relate to people and make them feel comfortable. Some of these cases are horrendous, but he is always able to be friendly and calm down the witness in order to get the information. It’s a rare talent.”

Mancusi’s technical skills and warm, jocular nature—he’s like a favorite uncle with a really, really interesting job and plenty of stories to tell about it—have been called on in a variety of high-profile cases. One of the most famous was the case of the Stuyvesant Town Rapist, in which a man attacked several women at knifepoint in an East Side apartment building over a three-month period in 1993 and 1994. Mancusi’s interview with a victim led to a composite sketch that bore a startling likeness to the half-brother of a Miami assistant district attorney. After viewing the sketch on a wanted poster, the woman turned in her sibling, Anthony Monagas, who was arrested near her home. He was sentenced to forty years in prison—a severe punishment that took into account both the New York crimes and a previous series of rape convictions in Florida.

In 2007, Mancusi created a sketch of the man who gunned down thirty-four-year-old Daniel Malakov. The Queens dentist was shot twice in the chest as he took his four-year-old daughter, of whom he had just won custody in a bitter divorce dispute, to a Forest Hills playground to meet her mother, Mazoltuv Borukhova. A witness who had been walking her dog in the park at the time of the murder sought out Mancusi. Although she was initially too shell-shocked to offer useful details, the artist was able to create the relaxed environment necessary for a successful interview. By the time Mancusi finished, his portrait revealed the face of Borukhova’s uncle—who was later arrested after the fingerprints on the gun silencer found at the scene were matched to his own. Borukhova was charged with second-degree murder and conspiracy.

Over the years, Mancusi has also provided hundreds of age-progression renderings of kidnap victims and on-the-lam suspects, postmortem reconstructions of unidentified murder victims, and demonstrative evidence for court presentations. While interest in the lab side of crime scene investigation has exploded since the advent of CSI and other procedural TV shows, Mancusi maintains that students are not signing up in droves to become forensic artists. The field might be less “glamorous,” but to Mancusi, it’s extremely rewarding. “The DOA stuff is gruesome—no doubt about it. And sometimes it’s hard to see, let alone work with, a victim who’s still injured from something only a few hours earlier,” he understates, switching into just-the-facts policeman mode. Then he pauses, and his tone softens. “But the ability to create an image that really has no artistic value but can help get a suspect into custody, that’s huge. You feel a lot of accomplishment there.”

Mancusi’s achievements don’t stop at his forensic art. For his entire career, he has also freelanced as a commercial and fine artist, using acrylics to paint mystery-novel jackets (most for Holliday House), oils for posters of vibrant retro-style street scenes, pastels for portraits, pencil sketches and 3-D imagery for History Channel shows, and digital art for print companies, including a new series of colorful African-influenced pieces. “I found that I needed to have a lot of different oars in the water to make money,” he says. “I wasn’t really a master at anything. When one technique made money for me, another didn’t. I’d do some acrylics and pastel work would die. Then I’d get some pen-and-ink work. I let the media govern the way my images come out.”

Now that he’s retired from the force, Mancusi, whose home and art-crammed studio are in Peekskill, would like to get back to more of the inventive pieces he made so prolifically in college. Still, forensic projects for the NYPD—which he jokingly refers to as his “Medici family”—continue to be the main focus of his work. He also offers online and in-person courses in composite art, and has recently been approached by a book publisher to write a guide on the topic. The irony of all these unusual opportunities isn’t lost on him. “What I’ve found is that if you want to be an artist, more than anything you have to be ready to run through a door when it opens,” he observes. “You have to be ready to work—because it is work. Most people can’t just prop up a canvas and, boom, art—like Peter Max. That’s one of the problems with art today: A lot of people have stepped past the work, the process, and are going for the impact. If there’s no depth to the experience of getting to the impact, is it worth it? Even Picasso knew painting technique. You’ve got to learn traditional art, how color works, what is form, what is composition.… And then maybe you can be Peter Max.”

He pauses thoughtfully, smiles, and says, “I don’t know if I’ll ever get there, but I know I’ll never be bored.”

For more information on Stephen Mancusi’s work, visit www.forartist.com.

((sidebars))

Composite Art

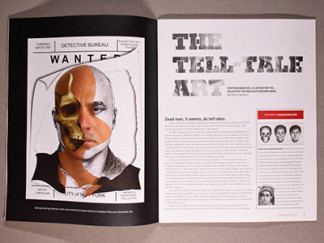

Used to create a single image from individually described parts, composite art requires skills in both drawing and police investigative work. Through careful questioning of the witness, often over several hours, the composite artist creates a facial rendering of a suspect. One of the most common misconceptions of this type of art is that it’s an exact portrait of the “bad guy.” Mancusi explains, “It’s a drawing of a witness’s perception of someone at the time they saw them. It’s a drawing of a memory.” In the 1994 case of the Stuyvesant Town Rapist, a victim’s memories of attacker Anthony Monagas (right) helped Mancusi create the sketch (left) that eventually led to his arrest and conviction.

Age Progression

This type of image modification alters a photograph to postulate what a subject might look like some years in the future. The artist must have knowledge of the specific effects of human aging in order to create a detailed portrait. Age progression is often used in child kidnapping cases, and in situations when an outstanding arrest warrant exists for a subject who hasn’t been photographed for several years. There are also entertainment applications for image modification, as seen here in Mancusi’s age progression of actress Meg Ryan, part of a series commissioned by Entertainment Weekly to project how certain celebrities might appear if marooned on an island like Tom Hanks’s character in Cast Away.

Postmortem Reconstruction

When an unidentified body or set of skeletal remains is discovered, police investigators sometimes rely on a forensic artist to create a postmortem reconstruction. Based on in-person observation, study of morgue photographs, and/or information from a medical examiner (or, in the case of skeletal remains, a forensic anthropologist), the artist produces a digital sketch or clay model of the deceased’s facial features, to approximate how he or she may have looked when alive. The less tissue and the more bone that are present, the more subjective the rendering becomes. Mancusi’s reconstruction of this homicide victim led to his identification.

Demonstrative Evidence

This refers to the visual materials used during legal proceedings as courtroom presentations or investigative aids, and can encompass everything from one-dimensional diagrams on illustration boards to digitally animated crime-scene reenactments. This rendering, the final frame of a multimedia presentation of a gunshot murder, illustrates the positioning of the victim’s body, the locations of the entrance and exit wounds, and the bullet trajectory.