Why I’m Not an Influencer

Yep, that’s me, looking decidedly non-influencer-like on a trip to Spain last year.

I just came back from a conference in California where a significant number of the speakers and attendees were influencers or aspiring influencers—people with many thousands, sometimes many hundreds of thousands—of followers on social media, and who often make a living through paid “collaborations.” Although I was speaking at the conference (for a second consecutive year) and was confident in the information I’d come to share, networking in rooms full of poised, sleekly coiffed, ever-camera-ready people really underscored something I’ve been telling clients for years: I’m not an influencer.

And I don’t want to be one.

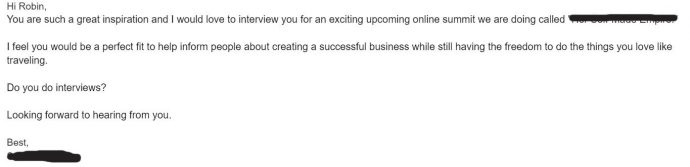

This thought was driven home just a few days ago. I had gotten the following e-mail through my website:

I didn’t recognize Sharon, the sender, and couldn’t fathom how she could be so inspired by someone she’d never met, so my bullshit meter immediately tipped into the red. I figured she probably wanted to sell me something, but, hey, exposure to a new market isn’t necessarily bad, right? So after some back and forth, we planned a post-conference phone conversation.

After some business chitchat and my asking questions about said exciting online summit—a series of interviews with successful female entrepreneurs—Sharon said, “You have a mailing list of at least 5,000, right?” I told her I didn’t; in fact, my mailing list was more like 400 and my combined social media following in the 2,000 range. Sharon, explaining how it “wouldn’t be fair” to the other presenters to include someone with such paltry numbers, then hightailed it off the call faster than my cat comes running when I crack a can of sardines.

My immediate reaction—after I controlled the urge to drop some F-bombs on Sharon—was anger. That quickly melted into disappointment and a feeling of inadequacy that my successes in business—especially as a female entrepreneur, her exact demographic—could be negated by the size of my following. Once I calmed down, I realized it was just one more reminder why not being an influencer can be a conscious choice, just like pursuing influencer status often is.

In his similarly-titled article on Influencive, digital marketing expert Dennis Yu, who actually has the numbers of an influencer, explains that he eschews the label partly because he doesn’t need it, and partly because it’s, well, a little ridiculous. He goes on to explain that being an influencer is not actually a metric of how successful you are in business—or even how skilled or knowledgeable you are. He writes:

“When you see these lists of the top ‘influencers,’ substitute these more accurate words to see how silly they sound:

- Forbes Top 100 list of the most awesome

- Social Media Examiner’s list of the people trying the hardest to appear famous.

- 50 people that are hoping to sell books and consulting, but don’t actually have specific things they can teach or implement.”

In closing, Yu says, “If you’re truly an influencer, your focus is on helping others instead of promoting yourself.”

This is not to dump on everything influencers do. As blogger Jeffrey Spivey of Uptown Bourgeois puts it, “I have nothing against influencers. I don’t find their societal contribution to be particularly noble, impactful, or useful. But I respect them for finding and maximizing income opportunities in this new space. It’s a bold, emerging form of entrepreneurship. But for me, if I have 7,000 people paying attention to what I’m saying, I want to make it count.”

Like Yu, I’m less interested in being a tastemaker or getting free stuff than I am in writing a memorable article, receiving a thank-you note from a workshop participant or student who had great results after taking my class, or providing sound, actionable advice to a client with limited resources—my definition of making it count.

I also don’t believe that our current preoccupation with numbers is a healthy way to evaluate success. It leads to equating those racked-up hearts and empty comments such as Me likey! or Awesome! or a string of emojis with meaningful interactions, wherein your audience understands anything about your brand or what you’re promoting. It deceives us into believing that these one-shot OMG! Have to haves will result in brand loyalty. Instead of celebrating all those square pegs who refuse to fit into round holes—and do something gloriously new or valuable because of it—it leads to a flock mentality that’s no more useful than a high school clique.

In her hilarious send-up on the New Yorker, Danielle Gibson’s faux influencer recounts, “When I really dug into what it is I’m truly passionate about, I realized that it’s not inspiring people through my creative outfits or positive mantras about personal well-being. What am I most deeply passionate about? Authentic brand partnerships.”

That’s the crux of the problem, isn’t it? While influencers used to have a lot more latitude to use the products they wanted, when they wanted, and say what they wanted about them, in order to keep up with the new wave of competing influencers, they’re constantly pressured to make every moment Insta-worthy, to assume that each thought and idea is worth expressing out loud. This turns even the most mundane things into a partnership moment, a “creative collaboration” that’s often anything but.

(As for authenticity . . . don’t get me started on the rank misuse of this word in marketing.)

Influencers may not agree with Spivey’s assertion that “To be an influencer is to get this unnatural high from being followed and praised by complete strangers. It serves this undying need to sit at the popular table in the cafeteria.” But having toiled behind the scenes to make some of the businesses I’ve worked for into brand influencers, I can tell you that there’s something to his theory about this type of work.

And it is work. Growing a following organically—without a megabucks ad budget, the use of bots, or paying for mailing lists—is a joyless, thankless, always-on grind that does give you a little high at first. Cut to a few months later, when you’re answering Facebook comments at 10:00 p.m. in your pajamas, jumping every time your phone dings with a push notification, and growing excited when you gain a handful of new followers—only to feel your heart drop when you inevitably lose a few. It feeds into our culture’s worst TMI tendencies, and Western society’s insatiability for more, more, more. When is who we are and what we have enough?

You might be thinking, You’re just saying you don’t want to be an influencer because you can’t be one. People aren’t interested in following you. And you might be right.

But people do want to hire me, and pay me good old American dollars to consult on their content strategy, and create articles and blog posts and e-mails, and work on a happy jumble of other interesting projects that not only pay my bills, but also leave me with enough left over for nice vacations and dinner with friends and the occasional little gift for myself, just because. They develop relationships with me and sometimes end up working with me for months or years on end. They remember me, and my name is the first to roll off their tongues when a colleague is looking for someone with my skill set. They are the reason that I’ll be able to retire early, and enjoy doing whatever I please for the rest of my ever-loving days.

The best part? I’m not working 70-hour weeks or tethered to my phone 24/7 to get there. I don’t have to style my acai bowl for the camera before eating it, or rack my brains over how to shoehorn a pomegranate facial peel into my next blog post. I can take a walk in the middle of the morning, or read a book for two hours in the afternoon. I can start work before the sun rises and quit while it’s still high in the sky—without even the teensiest bit of guilt that I haven’t checked my Twitter feed or Google Analytics.

For me, this is success: I’m working smarter, not harder, and doing work that matters to me, with people who deserve every bit of the effort I can give them. At the end of the day, I turn off my phone, turn out the lights, and spend time being the non-work me—which makes the work me even more effective.