Dance Review: Nicola Gunn in “Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster”

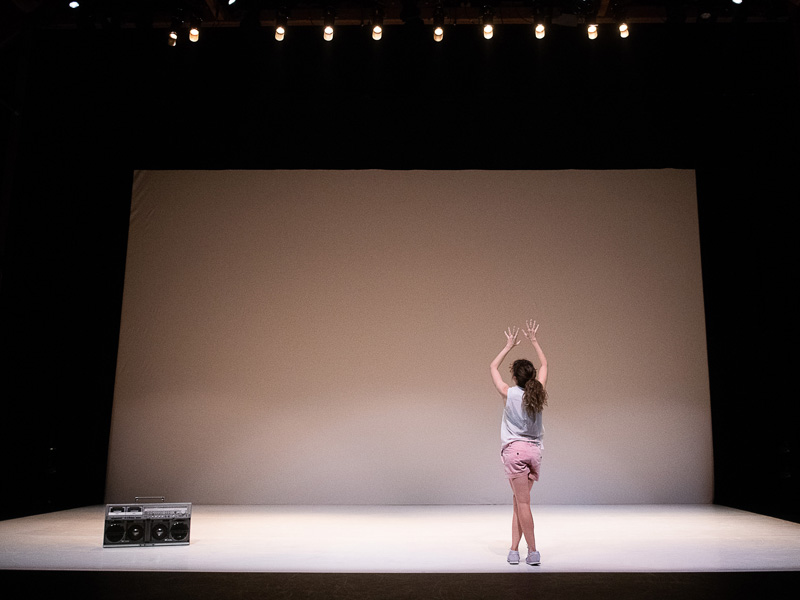

Nicola Gunn in “Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster” (photo by Christopher Duggan, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow).

Jacob’s Pillow, with its storied history of bringing classical and contemporary dance to both art lovers and mainstream audiences, seems like an unusual venue for Aussie artist Nicola Gunn’s Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster. More performance art or theatrical experience than dance performance, Piece for Person is a dynamic, subversive, often hilarious look at relationships between humans and themselves, and how they process both their outer and inner experiences.

Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster begins with Gunn’s narrator relating the dilemma of running along a lake in Belgium and happening upon a man who is throwing rocks at a stationary duck. It doesn’t sound like the setup for an hour’s worth of jokes and wry observations, but in Gunn’s deft comedic hands, the story builds and develops, and, like all good circular narratives, comes back to the same themes: free choice to act, whether necessarily or unnecessarily; a personal sense of justice that we may or may not apply to ourselves; and guilt.

Nicola Gunn in “Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster” (photo by Noor Eemaan, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow).

This allows Gunn ample time to do what she does best: go off on ridiculously funny tangents that take aim at her relationship with her mother (to whom she explains that she has personal policy to not contribute to overpopulation of the earth when she actually just doesn’t like children), British actor David Suchet (whom she paints as a pompous narcissist), and iconic Yugoslavian performance artist Marina Abramovich (who receives an especially brutal ripping for her apparent obsession with her legacy). Throughout, Gunn pokes holes at our personal vanity and the lies we tell ourselves and others.

The choreography of Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster, by Australian artist Jo Lloyd, is earthy, elastic, and tireless; Gunn must do some heavy-duty cardio to handle the two-fer of nonstop movement and nearly nonstop narration. Like the plot, the abstract choreography relies on thematic repetition. Sometimes this makes a powerful statement; other times, it’s oddly detached—movement for movement’s sake. Still, the majority of the show—including when Gunn invades the personal space of audience members by climbing over their chairs—is a kick both to watch and listen to, and provides more than a few thought-provoking moments.

Nicola Gunn in “Piece for Person and Ghetto Blaster” (photo by Christopher Duggan, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow).

The last ten minutes, which come off like a third-tier rave at Burning Man—complete with glittering costumes and strobe lights, loud ambient sound, and repetitive movement (literally the same movement over and over)—feel tacked-on at best and self-indulgent at worst. After an hour of frequently excellent performance, it’s a shame to leave viewers wondering when the performance will finally, mercifully, end. Gunn describes the latter part of the show as her character “finding transcendence and release from the human narrative.” (She also talks about other parts of the performance in her post-show Q&A with dance scholar Maura Keefe.) This may be the intention, but a sense of moving into lightness doesn’t come across from the audience. Just like the guilt-ridden protagonist of the narrative, Gunn is, it seems, her own worst enemy, and prone to unnecessary action.