Business Tip: Think Twice Before Signing That Freelancer Noncompete

As a freelancer, you’ll have your own contracts for work you do for smaller clients. Larger clients, on the other hand, will have extensive and detailed contracts of their own for you to sign. These can be so lengthy that it’s tempting to give them just a passing glance, like you probably did when you first signed up for accounts with Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. But assuming the client has your needs and rights in mind is a mistake—not because clients are consciously trying to stick it to freelancers, but because they’ve usually had their contracts developed by overzealous law firms who are in the business of protecting their clients’ business, no matter the cost to the people those businesses work with. While you should carefully read every bit of your contract and question anything you don’t understand or agree with, one area that warrants special attention is the freelancer noncompete clause.

In essence, a noncompete, sometimes called a covenant not to compete, says that you agree not to enter into another business agreement or start a business that directly competes with the company in question. Noncompetes were originally developed to prevent an employee from leaving a company and taking that company’s customers or trade secrets with them, or starting a new business that targets the same audience. For companies that make their living through selling product or intellectual property they create, noncompetes are a must.

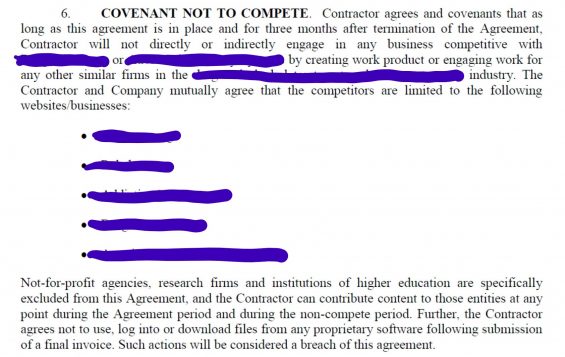

Here’s an example of a freelancer noncompete, from a company I’ve done some work for:

For on-staff employees of companies that sell product or intellectual property, noncompetes present a sticky situation. If the employee wants to stay in her current industry once she leaves her job, she either has to get permission from the employer to break the noncompete, or else she has to avoid taking a similar job in the same industry for the entire term of the noncompete—usually one year. That’s a long time to go without applying for jobs that are similar in scope and day-to-day work to the one you’ve been working hard at, possibly for several years or more, and are most qualified to do.

For the freelance contractor, the noncompete is a truly raw deal, because it restricts the freelancer—who may be in the early stages of building a writing business, or other creative business—from applying for or accepting work projects with competing companies even after the freelancer’s work with the original company is long over. And since freelancers make their living in part by being able to take on work from a variety of sources, signing a freelancer noncompete can mean a loss of wages for months or even years.

To give you some context, for my last on-staff position, I went to work for Home Décor Company A. I so badly wanted to get away from my previous job that I barely read the contract that was put in front of me. Huge mistake.

After five years of putting up with the exhausting antics of the jefa loca at Company A, I struck out on my own . . . and quickly realized that I couldn’t capitalize on the skills and industry knowledge I’d developed in the home décor world to get a similar job with another company—all thanks to a yearlong noncompete. Yes, I could do different types of work within the industry, but that’s not always easy to come by when you’ve spent several years specializing in a particular type of work. And why should a person—employee or contractor—have to reinvent the wheel with every job move?

Cut to a year and a half after I’d started my freelance copywriting and content marketing business. A guy who runs a small marketing agency we’ll call Boutique B found me in online search and contacted me about doing some contract work for his company, which handles a variety of different clients in a range of industries. Mr. Overreaching Owner and I had several e-mail and Skype conversations, all of which seemed to point to a productive working relationship. In addition, his pay rates were good and he was promising a steady stream of work over the next six months.

And then he sent me his freelancer agreement.

This one had a noncompete clause of three years. So for three years after his working relationship with me ended, he expected me to not solicit or accept work from his clients, regardless of whether the client had terminated their relationship with Boutique B and found me in online search, just like he did. Alarm bells blaring, I told him I could agree to no more than one year on a noncompete (which is still too long; we’ll get to that in a minute). Mr. Owner didn’t reply. I walked away, knowing I was passing up well-paying retainer work—the gold standard for many freelancers. But the potentially more significant long-term cost couldn’t justify my signing away my rights to work.

So what can a freelancer do to protect herself and her ability to generate income from the skill set she’s developed while working for different clients? Be aware of whether noncompetes are legal in your state; they are in most, but not all. And because they’re a reality of most freelancer contracts—and it’s unlikely the client will be willing to remove the clause completely—your job is to negotiate the terms of the freelancer noncompete as narrowly as possible.

First, don’t be fooled by the final-and-official look of the contract; the terms of almost all contracts are negotiable. If they’re not, think long and hard about whether this is a company you want to work with. Are they really worth giving up your ability to pay your bills by doing what you do best?

Second, once you’ve read through the contract, pull out the clauses in question—including the noncompete—and copy them into a new document or an e-mail for easy reference. Then politely outline what you would like those clauses to say instead.

Third, zero in on the term of noncompete. My personal policy is to sign noncompetes lasting no longer than three months. If you’re new to the freelance game, you may not have as much leverage. Or you may not yet have hit that glorious age at which you no longer care what the general population thinks of you. Either way, it doesn’t hurt to ask. Most likely, the client will come back with another number—say, six months—that’s better, even if it isn’t ideal. Then you have to decide whether the new offer is favorable enough for you to sign on, or whether you want to give the negotiation one more try.

Fourth, ask to narrow the scope of the freelancer noncompete. In the example above, you’ll see that I asked the company to choose just a few competitors that I wouldn’t work for during or for three months after my agreement with them ended. They came up with a list of five. Given this client’s niche and the unlikely event that these five competitors would come knocking on my door, the terms were acceptable to me.

It’s possible the client will be completely rigid and won’t agree to any concessions; I’ve come across just a few of those in my time as a freelancer, but they do exist. Unless they’re offering bucketloads or money, priceless connections in your industry, or some other version of the golden carrot, don’t be afraid to take your expertise elsewhere. Yes, it’s hard to turn down paid work, but it’s even harder to make up for lost time. And if independent contractors stick together in protecting our rights by saying no to unreasonable contract terms, eventually those unreasonable terms—including crazily restrictive freelancer noncompete clauses—will become a thing of the past.