What Lies Beneath: Sarah Pike Elevates Laser Cutting to Fine Art

The term laser cut has become ubiquitous in fashion and home décor over the past decade, with everything from patterned earrings and handbags to wall art created with machines that can inexpensively, if generically, cut large quantities of materials in minutes. But in the hands of Sarah Pike, founder of FreeFall Laser, the often-untapped capabilities of the laser cutter are elevated to fine art.

Pike started out as a painter and printmaker who managed the print studio at Bennington College for ten years. There she was drawn into the hands-on, multistep process of lithography, the most difficult type of printmaking, where ideas can gestate and take new directions while a project is in progress. When the college purchased a high-end laser cutter, Pike immediately recognized another avenue for artistic exploration. She studied with master cutters in the United States and abroad, and began experimenting with using the laser cutter to engrave, mark, or cut; fix pigments; and create other unique effects.

In 2016, Pike left academia, leaping, as she puts it, “without a parachute,” into FreeFall Laser. The studio, on Main Street in North Adams, affords inspiration right around the corner in the form of MASS MoCA, and also gives her access to a network of artists. They’re her primary clientele, with bookbinders and artist bookmakers, furniture conservators, and jewelers calling on her to help realize their vision.

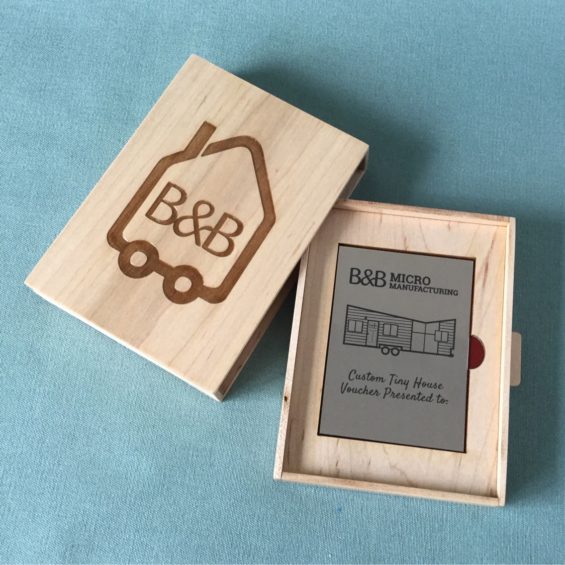

This voucher was commissioned by a client, who gifted a tiny house to her husband for his birthday. Pike created the maple box with sliding drawer, engraved the company logo on the box lid, and laser-marked the stainless steel voucher inside.

“A big part of growing a business is growing the community around the business,” Pike says. “What’s been most effective for me is surrounding myself with interesting artists and artisans who may or may not become clients—gathering people around me who have creative energy, and then building those relationships.”

Unlike the lasers used to create mass-market products, Pike’s Universal Standard laser cutter can be programmed with up to eight settings at a time, which vastly expands the effects that can be achieved by varying how the laser interacts with different surfaces—revealing, for instance, the subtleties of a wood grain in a way that a knife or a chisel could never do.

Clients usually come to FreeFall with a developed design or an idea, but often don’t know how to get from A to Z. Pike says, “With laser cutting, much more is possible than what’s in the general knowledge base. I listen to the specifics of their project, without judging them for not being tech-savvy, or looking down on an artistic idea that may not naturally lend itself to the laser technology. I’m more interested in problem-solving a final result.”

For the rotating-panel Revelation by Philadelphia-based artist bookmaker Thomas Parker Williams, Pike laser-cut the “pages” to reveal different word combinations as the central knob is turned.

Several steps and many hours of prep work go into creating a finished product. Pike’s pieces are usually smaller parts of a larger handcrafted whole and must integrate seamlessly with the client’s creation, which requires her to have knowledge of woodworking, painting, bookbinding, and other art forms—and serve as the bridge between the art and the laser cutter. She explains, “There’s a popular misconception that laser cutting is punching a bunch of numbers into a machine. Like any tool—whether it’s a paintbrush or a planer—it requires understanding of the material you’re working with as well as how the tool works.”

This knowledge and appreciation of a variety of art forms—and willingness to try inventive approaches—is why clients trust Pike to take on complex projects. For example, she recently created ten precision-cut wood panels for the artist book Revelation by Thomas Parker Williams. When the central knob is rotated, dozens of different word combinations are produced by revealing the digital prints beneath.

Pike was also hired to recreate the missing monogram inlays for a pair of nineteenth-century piano stools. She first examined the recessed areas in the stools, as well as the style of the inlays on other furniture in the same museum collection. From there, she transformed the conservator’s drawings into a digital file that could be read by the laser cutter.

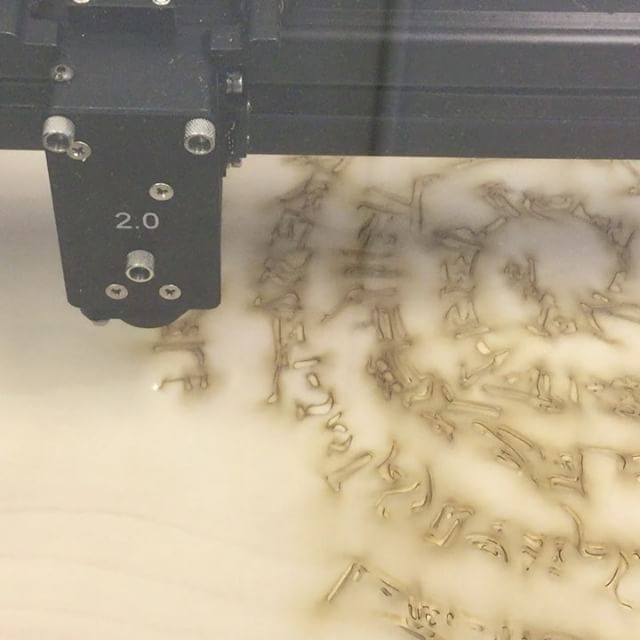

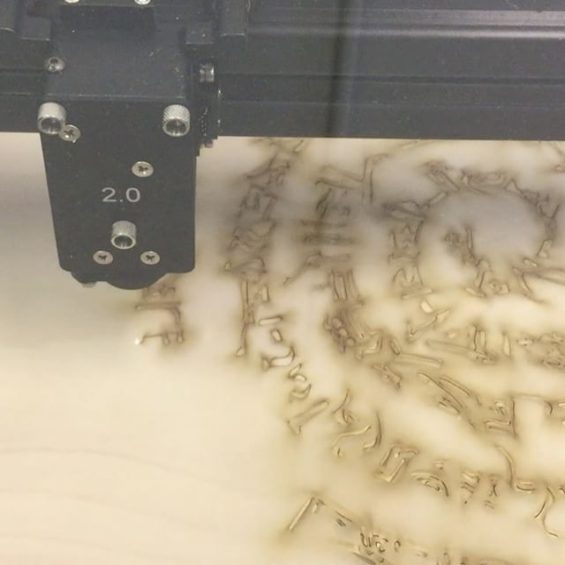

Pike developed a new laser-cutting method, called vapor printing, for Boston artist Naoe Suzuki. First Pike places a sheet of vellum over the artist’s painting. As the laser cuts through the vellum into the painted surface, paint particles become vapor that attaches to the vellum, creating a unique halo of color around the cut edge.

Next up: extensive testing. Mother-of-pearl was the first choice, but its thin, brittle character was no match for the heat of the laser, and the pieces ended up disintegrating. Pike then test-cut several different types of wood. “Every wood behaves differently with the heat of the laser, so we had to figure out the best way to cut each,” she notes. Ultimately, pear, boxwood, and cedar were chosen for the project, with some pieces cut right-side-up and some cut upside-down to create a dovetailing effect when the pieces were arranged together.

Though Pike delights in the meticulous engineering of projects like these, even more, she enjoys the revelatory potential of using the laser to expose what lies beneath the surface of a material, from the clean white “canvas” in laser-engraved areas of dark-colored parchment to engraving on fabric to remove the top layer of dye and expose the undyed material underneath. “I like to experiment with working within the confines of a medium while augmenting what we have,” says. “What happens when we remove those layers? Or when we move the focal distance on the laser? How can I spark something that will help the artist think more expansively and integratively about her medium?”

This article first appeared in Berkshire HomeStyle.