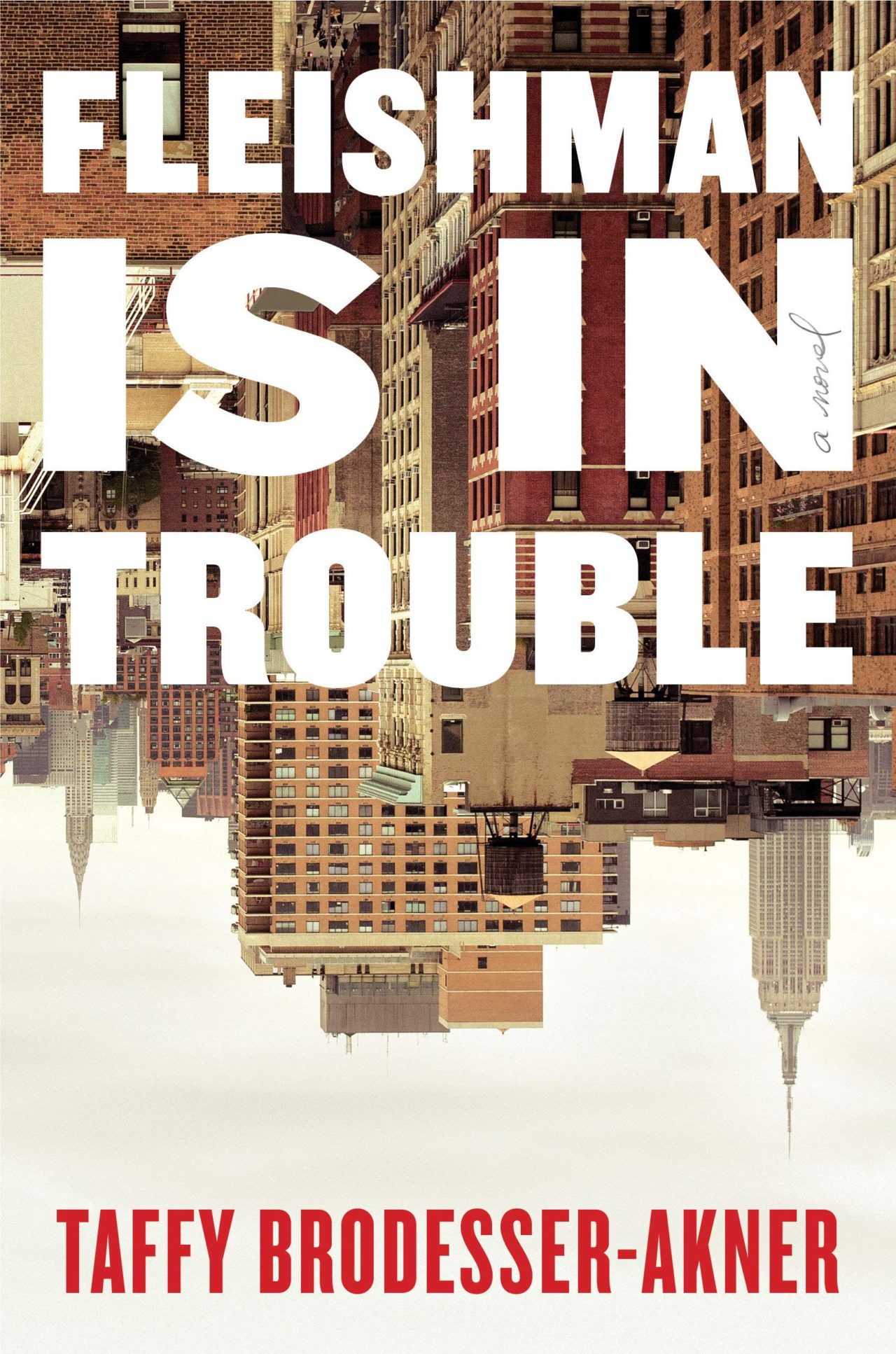

Book Review: Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner

There are a few universal truths about divorce. It’s always unequal, with one person doing the leaving and the other person being left. It’s a legal headache, from the dissolution of the relationship to the division of everything from assets to furniture, to financial entanglements like alimony and child support. If there are kids in the relationship, they inevitably end up caught in the middle, no matter how hard parents try to keep them out. And even when it’s good, there’s really not much that’s good about such a split, save that two (probably) mismatched people might have the opportunity to eventually find a better match—or just spend some time alone.

This often acrimonious, usually painful, and sometimes exhilarating world is the setting for Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Fleishman Is in Trouble, which made many critics’ top ten lists for 2019. A small drama about big issues, it’s a remarkable look at how we behave both behind closed doors and out in the open when our primary relationship doesn’t just end, it implodes, and we’re left to rediscover who we really are.

Fleishman is built on a series of dualities. There’s the seemingly have-it-all couple who fall apart at the seams. There’s the mostly pulled-together exterior lives of both Rachel and Toby, contrasted with their increasingly messy interior lives (which leads to some cringe-inducingly realistic poor decision making, and its repercussions). Then there’s the title, which is used a couple times to describe Toby’s mental alarm-ringing over his own situation, but it actually seems applicable to Fleishmans. And the book itself is divided into two parts, examining Toby’s search for validation and affection through a string of dating apps and Rachel’s burying herself in work and an ever-shrinking circle of friends.

Fleishman Is in Trouble depicts a significant role reversal, putting Toby into the traditional female role and Rachel into the man’s. While this might seem to set Rachel up for a more successful time of it, the novel turns an unsparing glance on how women fare in a patriarchal world. To wit: “You still had to tiptoe around the fragility of a man, which was okay for women who got to shop and drink martinis all day—this was their compensation; they had done their own negotiations—but was absolutely intolerable for anyone who was out there working and getting respect and becoming the person other people had to tiptoe around.”

Other passages question the inherent worth of women. “The world diminished a woman from the time she stopped being sexually available to it, and there was nothing to do except accept that and grow older,” writes Brodesser-Akner in one spot. In another, she takes aim at the idea that women can be appreciated as multidimensional beings: “Whatever kind of a woman you are, even when you’re a lot of kinds of women, you’re still always just a woman, which is to say you’re always a little bit less than a man.”

It’s truthful and compelling, and Fleishman is at its best when unmasking these social negotiations. Brodesser-Akner is a sharp-eyed observer of the lies we tell—to self and others—while in the midst of relationship turmoil. Anyone who’s been through it will immediately relate to the obsessive thinking, the anger directed at one’s partner, the pain of a major identity shift, and the discomfort that comes when what we think should feel like freedom ends up feeling more like a boat that’s come unmoored from its dock. Anyone who hasn’t been through such a split will no doubt feel empathy, and maybe even a desire to love their partner a little bit better.

But Fleishman’s greatest strength is also its weakness: it’s so good at depicting the swirling interior life of the recently divorced, from the desperation for validation to the search for affection, from the unsatisfying ups to the bitter downs, that the majority of the book takes places in the minds of its two main characters. Sometimes it’s moving; other times it’s repetitive and exhausting (like an actual divorce, true. But as entertainment? Trying). And the setup for Toby’s story, full of barely concealed ego and half-truths, is so long that by the time we get to hear Rachel’s perspective, our patience has grown thin, and her story gets short shrift.

It becomes clear later on that in Fleishman Is in Trouble, Brodesser-Akner is trying to juxtapose the deep unhappiness of the divorcing Rachel and Toby with the restless search for identity of the narrator Libby, who seems to come alive fairly late in the game. But because she appears in the story only after 20 pages or so and then pops up again periodically in first person, it feels intrusive. Like her husband Adam, a seemingly nice guy Libby just can’t be entirely happy with, the book might be better off without her. We’d still have plenty of Toby and Rachel’s interior scenery to chew on.